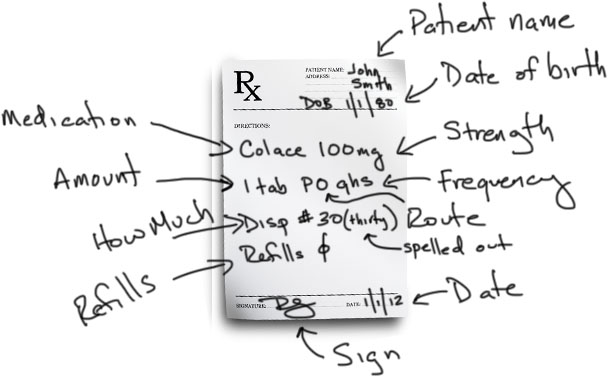

Prescriptions

A prescription is an order that is written by you, the physician (or medical student with signature by a physician) to tell the pharmacist what medication you want your patient to take. The basic format of a prescription includes the patient’s name and another patient identifier, usually the date of birth. It also includes the meat of the prescription, which contains the medication and strength, the amount to be taken, the route by which it is to be taken and the frequency. Often times, for “as needed” medications, there is a symptom included for when it is to be taken. The prescriber also writes how much should be given, and how many refills. Once completed with a signature and any other physician identifiers like NPI number or DEA number, the prescription is taken to the pharmacist who interprets what is written and prepares the medication for the patient. Let’s break it down.

Patient Identifiers

According to the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) national patient safety goals, at least two patient identifiers should be used in various clinical situations. While prescription writing is not specifically listed, medication administration is. I think prescription writing should be considered in this category as well. The two most common patient identifiers are full name and date of birth. These are the FIRST things to write on a prescription. This way you don’t write a signed prescription without a patient name on it that accidentally falls out of your white coat and onto the floor in the cafeteria.

[ads1]

Drug/Medication

This is an easy one. This is the medication you want to prescribe. It generally does not matter if you write the generic or the brand name here, unless you specifically want to prescribe the brand name. Remember, if you do want the brand name, you specifically need to tell the pharmacist – “no generics.” There are several reasons why you would want to do this, but we won’t get into that here. On the prescription pad, there is a small box which can be checked to indicate “brand name only” or “no generics”.

Strength

After you write the medication name, you need to tell the pharmacist the desired strength. Many, if not most, medications come in multiple strengths. You need to write which one you want. Often times, the exact strength you want is not available, so the pharmacist will substitute an appropriate alternative for you. For example, if you write prednisone (a corticosteroid) 50 mg, and the pharmacy only carries 10 mg tablets, the pharmacist will dispense the 10 mg tabs and adjust the amount the patient should take by a multiple of 5.

Amount

Using my previous example for prednisone, the original prescription was for 50 mg tabs. The prescriber would have written “prednisone 50 mg, one tab….” (I’ll leave out the rest until we get there). The “one tab” is the amount of the specific medication and strength to take. Again using my previous example, the instructions would be rewritten “prednisone 10 mg, five tabs….” You can see that “one tab” was changed to “five”. Pharmacists make these changes all the time, often without any input needed from the physician.

Route

Up until this point, we have been using plain English for the prescriptions. The route is the first opportunity we have to start using English or Latin abbreviations. A NOTE: it is often suggested that to help reduce the number of medication errors, prescription writing should be 100% English, with no Latin abbreviations. I will show you both and let you decide. There are several routes by which a medication can be taken: By Mouth (PO), Per Rectum (PR), Sublingually (SL), Intramuscularly (IM), Intravenously (IV), Subcutaneously (SQ)

As you can see, the abbreviations are either from Latin roots like PO – per os – or just common combination of letters from the English word. Unfortunately when you are in a hurry and scribbling these prescriptions, (there is a truth behind never being able to read a physician’s hand writing) many of these abbreviations can look similar. For example, intranasal is often abbreviated “IN,” which, when you are in a hurry, can be mistaken for “IM” or “IV.” Check this out:

Common Route Abbreviations:

PO (by mouth)

PR (per rectum)

IM (intramuscular)

IV (intravenous)

ID (intradermal)

IN (intranasal)

TP (topical)

SL (sublingual)

BUCC (buccal)

IP (intraperitoneal)

[ads1]

Frequency

The frequency is simply how often you want the prescription to be taken. This can be anywhere from once a day, once a night, twice a day or even once every other week. Many frequencies start with the letter “q.” Q if from the Latin word quaque which means once. So it used to be that if you wanted a medication to be taken once daily, you would write QD, for “once daily” (“d” is from “die,” the Latin word for day). However, to help reduce medication errors, QD and QOD (every other day) are on the JCAHO “do not use” list. Instead you need to write “daily” or “every other day.”

Common Frequencies Abbreviations:

daily (no abbreviation)

every other day (no abbreviation)

BID/b.i.d. (Twice a Day)

TID/t.id. (Three Times a Day)

QID/q.i.d. (Four Times a Day)

QHS (Every Bedtime)

Q4h (Every 4 hours)

Q4-6h (Every 4 to 6 hours)

QWK (Every Week)

[ads1]

The “Why” Portion

Many prescriptions that you write will be for “as needed” medications. This is known as a “PRN” (from the Latin pro re nata, meaning as circumstances may require). For example, you may write for ibuprofen every 4 hours “as needed.” What is commonly missed is the “reason.” Why would it be needed? You need to add this to the prescription. You should write “PRN headache” or “PRN pain” so that the patient knows when to take it.

How Much

The “how much” instruction tells the pharmacist how many pills should be dispensed, or how many bottles, or how many inhalers. This number is typically written after “Disp #.” I highly recommend that you spell out the number after the # sign, though this is not required. For example: I would write “Disp #30 (thirty).” This prevents someone from tampering with the prescription and adding an extra 0 after 30, turning 30 into 300.

Refills

The last instruction on the prescription informs the pharmacist how many times the patient will be allowed to use the same exact prescription, i.e. how many refills are allowed. For example, let’s take refills for oral contraceptives for women. A physician may prescribe 1 pack of an oral contraceptive with 11 refills, which would last the patient a full year. This is convenient for both the patient and physician for any medications that will be used long term.

[ads1]

Leave a Reply